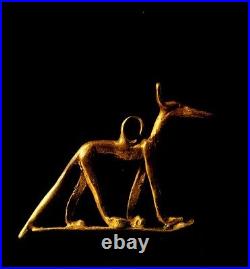

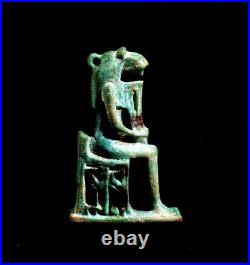

Symbolism Ancient Egyptian Amulets Osiris Isis Thoth Amun Sekhmet Horus Maat Bes

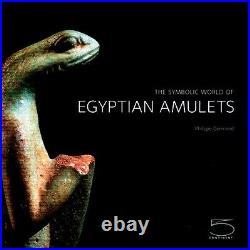

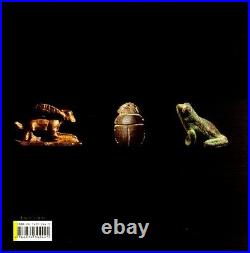

The Symbolic World of Egyptian Amulets by Philippe Germond. NOTE : We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition.

We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). We're happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

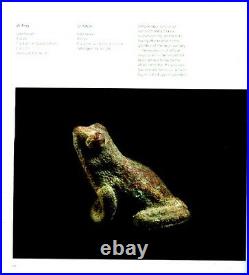

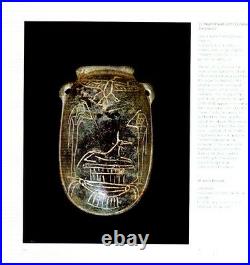

Size: 8¾ x 8¾ inches; 1¾ pounds. SUMMARY: The amulets of ancient Egypt are an extraordinary testimony to the unique originality and wealth of Pharaonic civilization. This intriguing book unlocks their symbolic secrets. Small as they are, they speak to us on many topics: the everyday cares of the Nile Valley peasant in an environment he has yet to master, the complexity of the pantheon and the sacred bestiary and the subtle physiognomies of royalty.

Using the approach pioneered by Jacques-douard Berger, ever sensitive to what the object has to say, we discover the outcome of an ardent quest for the'neter' - universal, divine harmony - through objects that communicate the nefer - the expression of all beauty and plenitude. Most of the amulets shown are on display in the Muse de Design et d'Arts Appliqus Contemporains (MUDAC) at Lausanne, where the Jacques-douard Berger collection is on long-term loan. Unblemished and pristine in every respect.

Pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightly bound, unambiguously unread. PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK. PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW. REVIEW : Philippe Germond, PhD (Egyptology) of the University of Geneva, President of the Egyptology Society, Geneva. Author of numerous articles and reviews in specialized journals and major books.

REVIEW : This book proposes to guide the reader in the exploration of a symbolic universe hidden in the amulets of ancient Egypt, those privileged testimonies of the essential originality and wealth of the Pharaonic civilization. REVIEW : Fabulous photos, excellent descriptions. A wonderful resource for those interested in ancient Egyptian amulets. REVIEW : Wonderful photo catalogue and accompanying text on the subject of Egyptian amulets. This is where I learned about the rabbit amulets and their relation to the Egyptian verb of being! Very good pics and text. REVIEW : The amulets I visited in NYC at the Metro still have some kind of hold on me. This book proved to be an excellent guide.HISTORY OF ANCIENT EGYPT : In the southwestern corner of Egypt, near the border of Sudan, archeologists find evidence of human habitation at least 10,000 years ago. Though this area once was blessed with grassy plains and lakes that formed during periods of seasonal rain, it is dry now.

We believe that by 6,000 BC the population kept herds of cattle and erected some large buildings. As the climate became more arid, these people migrated east and began what became the Egyptian civilization in the fertile Nile Valley.

By the time another 2,000 years had passed, this population had settled Upper Egypt in such locations as Hierakonpolis, Naqada and Abydos. By 3,300 BC ancient Egypt had established itself as one of the world's most advanced civilizations. It was destined to be one of the most long-lived as well. The source of the life-giving Nile River, which made ancient Egyptian civilization possible, is found in the highlands of East Africa.The river flows in a northerly direction through territory that is now Sudan and Egypt, forms a broad and fertile delta, and empties into the Mediterranean Sea. Every year, during seasonal rains "upriver" in south Africa, the Nile overflowed its banks, depositing rich black soil on the floodplain. This allowed the ancient Egyptians to establishing a thriving agricultural economy.

Other elements were conducive to the development of a great civilization. The Nile provided transport, a constant source of water that sustained plants, humans and animals, and the rays of the sun in mostly cloudless skies provided light and heat. An additional bonus came in the form of natural barriers that prevented invasion by hostile peoples: the desert to the west, the sea to the north and east, and the cataracts of the Nile to the south. Though other civilizations rose and faded in importance, Egypt alone survived for thousands of years, allowing the fruition of sophistication and creativity.

In this territory the two of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World are found; the pyramids at Giza and the lighthouse at Alexandria. The Egyptians produced an immense and sophisticated catalogue of literature that included treatises on ethical and moral behavior, "how-to" texts, works of religious and magical import, and quite a number of epic stories, ribald tales and love poetry. They understood the principles of mathematics and architecture and were able to erect large stone buildings prior to 2,500 BC.They originated the basic concepts of arithmetic and geometry and of medicine and dentistry as well. They developed a calendar based on their astronomical observations. Egyptian cultural and religious images, whether sculpted, painted or drawn, fascinate modern people everywhere.

Their early written form, known as hieroglyphics, is pictographic; symbols take the form of recognizable images. As for religious belief, the ancient Egyptian culture was one of the firsts to have a concept of life after death. They paid lavish attention to preparations for that life, perhaps more lavish and detailed than in any culture before or since and certainly more sophisticated. Royal and private remains were laid to rest in underground chambers erected for that purpose. Above the ground great pyramids were erected, as well as sprawling temple complexes and immense statues that combined human and animal forms.

Many survive today, though some were buried by the sands of time to come to light only much later. The study of ancient Egypt still consumes archeologists and scholars, who admit there is much yet to be learned about this fascinating culture. One contentious question concerns the origin of writing: Egypt or Mesopotamia?

While the written record attests to at least 3,000 years of Egyptian culture, the archeological evidence suggests a time frame of greater duration. ANCIENT EGYPTIAN AMULETS : One of the greatest civilizations of recorded history was ancient Egypt.

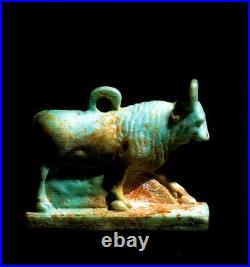

Ancient Egyptian artifacts (amulets, beads, and other forms of jewelry) are amongst the most sought after and highly collectible artifacts from ancient Egypt. Religion was very important to the ancient Egyptians, and they worshipped many gods. These gods and goddesses often represented the natural world, such as the sky, earth, sun, or wind. The gods took the form of animals or animal/human figures.The ancient Egyptians wore amulets, small representations of these gods, as magical charms to ward off danger. They believed that these amulets, or talismans, would not only protect them in life, but in death as well, and would endow the individual wearing them with magical powers and capabilities. While religious beliefs in ancient Egypt played a very important role in life, they played an even larger role in death.

The ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead prescribed 104 different types of amulets be buried with the mummy in order to protect the deceased on his or her journey into the afterlife. Typically pinned to or wrapped within their burial shroud, it was not uncommon to find even thousands of amulets in the possession of the mummified remains of more prominent members of that ancient civilization. Typically when mummifying the deceased, there could be as many as 80 layers of linen, and it was not unusual to place at least one amulet representation of each of the more significant deities within each layer.

As with the entire process of mummification and burial, the manufacture of amulets and the application of the magic spells for the benefit of the deceased, were almost always overseen by Egyptian priests. Amulets from ancient Egypt were buried typically for between 2,500 and 3,000 years before being unearthed inside of tombs within the last century or two. Amulets typically are between one-half and two inches in size.

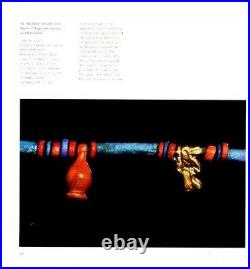

Amulets were oftentimes worn about the neck by the ancient Egyptians, typically on a beaded necklace. The beads were most often faience beads, in colors ranging from tan to pale jade green to cobalt blue. Though the material used to string the necklaces disappeared in the eons passed while buried within the tombs of Egypt, the beads themselves survived. ANCIENT EGYPTIAN FAIENCE : Faience, a primitive form of ceramic, was the ancient forerunner of modern glass, and was used by the Ancient Egyptians as far back as 3000 B. To fashion various amulets, beads, and other items of personal adornment. Most amulet/necklaces were both worn on a daily basis for protection, as well as buried with the dead to afford protection in the journey from this life to the next. Some bead necklaces were purely items of personal adornment, as these might have been so worn. Faience was produced by crushing quartz mixed with copper, and made into a paste. The paste was then placed in a mold, and then fired. The quartz would fuse, and the copper would give the resulting product a color with blue and/or green hues, which was favored by the ancient Egyptians as the color of the Nile River. ANCIENT EGYPTIAN FAIENCE : Egyptian faience is a glassy substance manufactured expertly by the ancient Egyptians. The process was first developed in Mesopotamia, first at Ur and later at Babylon, with significant results but faience production reached its height of quality and quantity in Egypt. Some of the greatest faience-makers of antiquity were the Phoenicians of cities such as Tyre and Sidon who were so expert in making glass that it is thought they invented the process.The Egyptians took the Phoenician technique and improved upon it, creating works of art which still intrigue and fascinate people in the present day. Faience was made by grinding quartz or sand crystals together with various amounts of sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and copper oxide. The resulting substance was formed into whatever shape was desired, whether an amulet, beads, a broach or a figurine and then said pieces were heated. During heating, the pieces would harden and develop a bright color which was then finely glazed. It is thought that the Egyptian artisans perfected faience in an attempt to imitate turquoise and other hard to find gem stones.

The calcium silicates in the mixture were responsible for the bright colors and the glassy finish. Among the most famous of faience statuary is the blue hippopotamus popularly known as "William", currently on exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, NY, USA. , both of the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom.

The figure was molded of faience and painted with river and marsh plants, representing the natural habitat of the hippo. A pasted of copper, limestone, and quartz oxide was then applied all over the figure which, when heated, turned it a bright blue. The hippo was considered an extremely dangerous animal by the ancient Egyptians and were sometimes included with grave goods (whether as statuary, amulet, or as an inscription) for protection of the deceased in the afterlife. The soul of the dead person, however, also required protection from its protecting hippo and some provision had to be made for this. In the case of "William" the Hippo, three of its legs were purposefully broken after the statue was completed so it would not be able to run after Senbi II in the afterlife and harm him.

Besides statuary, the Egyptians used faience for the manufacture of jewelry (rings, amulets, necklaces) but also for scarabs, to create the board and pieces for the game of Sennet, for furniture and even for bowls and cups. Among the most popular objects made from faience, however, were the Shabti dolls which were placed in the tombs of the dead. The Shabti was a figure, sometimes fashioned in the likeness of the deceased, who would take the dead person's place at communal work projects, ordained by the god Osiris, in the after-life of the Field of Reeds.

The Egyptian word for faience was tjehenet which means'gleaming' or'shining' and the faience was thought to reflect the light of immortality. The poor of Egypt, if they could even afford a Shabti doll, would have one made of wood, while the more wealthy and the nobility commanded Shabti of faience.

The colors of the faience (as with color generally) were thought to have special symbolism. Blue represented fertility, life, the Nile river on earth and in the after-life, green symbolized goodness and re-birth in the Field of Reeds, red was used for vitality and energy and also as protection from evil, black represented death and decay but also life and regeneration, and white symbolized purity.

The colors one sees on the Shabti dolls, and in other faience, all have very specific meaning and combine to provide a protective energy for the object's owner. So closely was faience associated with the Egyptian after-life that the tiles for the chamber walls of tombs were made of faience as was seen at King Djoser's tomb at Saqqara and, most famously, in the tomb of Tutankhamum where over one hundred objects were entirely or partially of faience. The earliest evidence of a faience workshop has been unearthed at Abydos and dated to 5500 B.The workshop consists of a number of circular pits, clearly the remains of kilns, with a lining of brick and all of them fire-marked. Layers of ancient ash in the pits are evidence of continuous use over many years. Small clay balls were also discovered and it is thought that they may have been used as the surface on which faience beads were fired in the kilns.

The names of the faience makers are lost to history save for one man, Rekhamun, who was known as "Faience Maker of Amun", and another known as Debeni, the overseer of faience workers. Of the other craftsmen in faience, and there must have been many, nothing is known.ANCIENT EGYPTIAN AFTERLIFE AND SHABTIS : Shabti Dolls (Ushabti): The Workforce in the Afterlife. The Egyptians believed the afterlife was a mirror-image of life on earth. When a person died their individual journey did not end but was merely translated from the earthly plane to the eternal. The soul stood in judgement in the Hall of Truth before the great god Osiris and the Forty-Two Judges and, in the weighing of the heart, if one's life on earth was found worthy, that soul passed on to the paradise of the Field of Reeds.

The soul was rowed with others who had also been justified across Lily Lake (also known as The Lake of Flowers) to a land where one regained all which had been thought lost. There one would find one's home, just as one had left it, and any loved ones who had passed on earlier. Every detail one enjoyed during one's earthly travel, right down to one's favorite tree or most loved pet, would greet the soul upon arrival. There was food and beer, gatherings with friends and family, and one could pursue whatever hobbies one had enjoyed in life. In keeping with this concept of the mirror-image, there was also work in the afterlife. The ancient Egyptians were very industrious and one's work was highly valued by the community. People, naturally, held jobs to support themselves and their family but also worked for the community.Community service was compulsory in `giving back' to the society which provided one with everything. The religious and cultural value of ma'at (harmony) dictated that one should think of others as highly as one's self and everyone should contribute to the benefit of the whole. The great building projects of the kings, such as the pyramids, were constructed by skilled craftsmen, not slaves, who were either paid for their skills or volunteered their time for the greater good. If, whether from sickness, personal obligation or simply lack of desire to comply, one could not fulfill this obligation, one could send someone else to work in one's place - but could only do so once.

On earth, one's place was filled by a friend, relative, or a person one paid to take one's place; in the afterlife, however, one's place was taken by a shabti doll. Shabti dolls (also known as shawbti and ushabti) were funerary figures in ancient Egypt who accompanied the deceased to the after-life.

Their name is derived from the Egyptian swb for stick but also corresponds to the word for `answer' (wsb) and so the shabtis were known as `The Answerers'. The figures, shaped as adult male or female mummies, appear in tombs where they represented the deceased and were made of stone, wood or faience.

Were made of stone or wood (in the Late Period they were composed of faience) and represented an anonymous `worker'. Each doll was inscribed with a `spell' (known as the shabti formula) which specified the function of that particular figure.

Citizens were obligated to devote part of their time each year to labor for the state on the many public works projects the pharaoh had decreed according to their particular skill and a shabti would reflect that skill or, if it was a general `worker doll', a skill considered important. As the Egyptians considered the after-life a continuation of one's earthly existence (only better in that it included neither sickness nor, of course, death) it was thought that the god of the dead, Osiris, would have his own public works projects underway and the purpose of the shabti, then, was to `answer' for the deceased when called upon for work. For the deceased providing guidance in the unfamiliar realm of the afterlife.The Book of the Dead contains spells which are to be spoken by the soul at different times and for different purposes in the afterlife. There are spells to invoke protection, to move from one area to another, to justify one's actions in life, and even a spell "for removing foolish speech from the mouth" (Spell 90). Among these verses is Spell Six which is known as "Spell for causing a shabti to do work for a man in the realm of the dead".

This spell is a re-worded version of Spell 472 from the Coffin Texts. When the soul was called upon in the afterlife to labor for Osiris, it would recite this spell and the shabti would come to life and perform one's duty as a replacement. The shabti would then be imbued with life and take one's place at the task. Just as on earth, this would enable the soul to go on about its business. Each of these shabtis was created according to a formula so, for example, when the spell above references "making arable the fields" the shabti responsible would be fashioned with a farming implement.

Every shabti doll was hand-carved to express the task the shabti formula described and so there were dolls with baskets in their hands or hoes or mattocks, chisels, depending on what job was to be done. In modern times, therefore, the number of dolls found in excavated tombs has helped archaeologists determine the status of the tomb's owner. The poorest of tombs contain no shabtis but even those of modest size contain one or two and there have been tombs containing a shabti for every day of the year. In the Third Intermediate Period circa1069-747 B.

There appeared a special shabti with one hand at the side and the other holding a whip; this was the overseer doll. During this period the shabti seem to have been regarded less as replacement workers or servants for the deceased and more as slaves. The overseer was in charge of keeping ten shabtis at work and, in the most elaborate tombs, there were thirty-six overseer figures for the 365 worker dolls.In the Late Period circa 737-332 B. The shabtis continued to be placed in tombs but the overseer figure no longer appeared. These shabtis were fashioned as the earlier ones with specific tools in their hands or at their sides for whatever task they were called upon to perform.

Shabti dolls are the most numerous type of artifact to survive from ancient Egypt (besides scarabs). As noted, they were found in the tombs of people from all classes of society, poorest to most wealthy and commoner to king. The shabti dolls from Tutankamun's tomb were intricately carved and wonderfully ornate while a shabti from the grave of a poor farmer was much simpler. It did not matter whether one had ruled over all of Egypt or tilled a small plot of land, however, as everyone was equal in death; or, almost so. The king and the farmer were both equally answerable to Osiris but the amount of time and effort they were responsible for was dictated by how many shabtis they had been able to afford before their death.

In the same way that the people had served the ruler of Egypt in their lives, the souls were expected to serve Osiris, Lord of the Dead, in the afterlife. This would not necessarily mean that a king would do the work of a mason but royalty was expected to serve in their best capacity just as they had been on earth. The more shabti dolls one had at one's disposal, however, the more leisure time one could expect to enjoy in the Field of Reeds. This meant that, if one had been wealthy enough on earth to afford a small army of shabti dolls, one could look forward to quite a comfortable afterlife; and so one's earthly status was reflected in the eternal order in keeping with the Egyptian concept of the afterlife as a direct reflection of one's time on earth. ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BURIAL : Egyptian burial is the common term for the ancient Egyptian funerary rituals concerning death and the soul's journey to the afterlife.Eternity, according to the historian Bunson, "was the common destination of each man, woman and child in Egypt" but not `eternity' as in an afterlife above the clouds but, rather, an eternal Egypt which mirrored one's life on earth. The afterlife for the ancient Egyptians was The Field of Reeds which was a perfect reflection of the life one had lived on earth. Egyptian burial rites were practiced as early as 4000 B.

And reflect this vision of eternity. The earliest preserved body from a tomb is that of so-called `Ginger', discovered in Gebelein, Egypt, and dated to 3400 B. Burial rites changed over time between circa 4000 B. But the constant focus was on eternal life and the certainty of personal existence beyond death.This belief became well-known throughout the ancient world via cultural transmission through trade (notably by way of the Silk Road) and came to influence other civilizations and religions. It is thought to have served as an inspiration for the Christian vision of eternal life and a major influence on burial practices in other cultures. According to Herodotus 484-425/413 B.

, the Egyptian rites concerning burial were very dramatic in mourning the dead even though it was hoped that the deceased would find bliss in an eternal land beyond the grave. He writes: As regards mourning and funerals, when a distinguished man dies, all the women of the household plaster their heads and faces with mud, then, leaving the body indoors, perambulate the town with the dead man's relatives, their dresses fastened with a girdle, and beat their bared breasts. The men too, for their part, follow the same procedure, wearing a girdle and beating themselves like the women. The ceremony over, they take the body to be mummified. Mummification was practiced in Egypt as early as 3500 B. And is thought to have been suggested by the preservation of corpses buried in the arid sand. The Egyptian concept of the soul - which may have developed quite early - dictated that there needed to be a preserved body on the earth in order for the soul to have hope of an eternal life. The soul was thought to consist of nine separate parts: the Khat was the physical body; the Ka one's double-form; the Ba a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens; Shuyet was the shadow self; Akh the immortal, transformed self, Sahu and Sechem aspects of the Akh; Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil; Ren was one's secret name.The Khat needed to exist in order for the Ka and Ba to recognize itself and so the body had to be preserved as intact as possible. After a person had died, the family would bring the body of the deceased to the embalmers where the professionals produce specimen models in wood, graded in quality.

They ask which of the three is required, and the family of the dead, having agreed upon a price, leave the embalmers to their task. There were three levels of quality and corresponding price in Egyptian burial and the professional embalmers would offer all three choices to the bereaved. According to Herodotus: "The best and most expensive kind is said to represent [Osiris], the next best is somewhat inferior and cheaper, while the third is cheapest of all". These three choices in burial dictated the kind of coffin one would be buried in, the funerary rites available and, also, the treatment of the body. According to the historian Ikram, The key ingredient in the mummification was natron, or netjry, divine salt.

It is a mixture of sodium bicarbonate, sodium carbonate, sodium sulphate and sodium chloride that occurs naturally in Egypt, most commonly in the Wadi Natrun some sixty four kilometres northwest of Cairo. It has desiccating and defatting properties and was the preferred desiccant, although common salt was also used in more economical burials. The second most expensive burial differed from the first in that less care was given to the body. No incision is made and the intestines are not removed, but oil of cedar is injected with a syringe into the body through the anus which is afterwards stopped up to prevent the liquid from escaping. The body is then cured in natron for the prescribed number of days, on the last of which the oil is drained off.

The effect is so powerful that as it leaves the body it brings with it the viscera in a liquid state and, as the flesh has been dissolved by the natron, nothing of the body is left but the skin and bones. The third, and cheapest, method of embalming was "simply to wash out the intestines and keep the body for seventy days in natron" The internal organs were removed in order to help preserve the corpse but, because it was believed the deceased would still need them, the viscera were placed in canopic jars to be sealed in the tomb. Only the heart was left inside the body as it was thought to contain the Ab aspect of the soul. Even the poorest Egyptian was given some kind of ceremony as it was thought that, if the deceased were not properly buried, the soul would return in the form of a ghost to haunt the living. As mummification could be very expensive, the poor gave their used clothing to the embalmers to be used in wrapping the corpse.

This gave rise to the phrase "The Linen of Yesterday" alluding to death. "The poor could not afford new linens, and so wrapped their beloved corpses in those of `yesterday'". In time, the phrase came to be applied to anyone who had died and was employed by the Kites of Nephthys (the professional female mourners at funerals). The deceased is addressed by these mourners as one who dressed in fine linen but now sleeps in the `linen of yesterday'. That image alluded to the fact that life upon the earth became `yesterday' to the dead (Bunson, 146). The linen bandages were also known as The Tresses of Nephthys after that goddess, the twin sister of Isis, became associated with death and the afterlife. The poor were buried in simple graves with those artifacts they had enjoyed in life or whatever objects the family could afford to part with. Every grave contained some sort of provision for the afterlife.Tombs in Egypt were originally simple graves dug into the earth which then developed into the rectangular mastabas, more ornate graves built of mud brick. Mastabas eventually advanced in form to become the structures known as `step pyramids' and those then became `true pyramids'. These tombs became increasingly important as Egyptian civilization advanced in that they would be the eternal resting place of the Khat and that physical form needed to be protected from grave robbers and the elements. The coffin, or sarcophagus, was also securely constructed for the purposes of both symbolic and practical protection of the corpse.

The line of hieroglyphics which run vertically down the back of a sarcophagus represent the backbone of the deceased and was thought to provide strength to the mummy in rising to eat and drink. Provisioning the tomb, of course, relied upon one's personal wealth and, among the artifacts included were Shabti Dolls. In life, the Egyptians were called upon to donate a certain amount of their time every year to public building projects. If one were ill, or could not afford the time, one could send a replacement worker.One could only do this once in a year or else face punishment for avoidance of civic duty. In death, it was thought, people would still have to perform this same sort of service (as the afterlife was simply a continuation of the earthly one) and so Shabti Dolls were placed in the tomb to serve as one's replacement worker when called upon by the god Osiris for service. The more Shabti Dolls found in a tomb, the greater the wealth of the one buried there. As on earth, each Shabti could only be used once as a replacement and so more dolls were to be desired than less and this demand created an industry dedicated to their creation. Once the corpse had been mummified and the tomb prepared, the funeral was held in which the life of the deceased was honored and the loss mourned.

Even if the deceased had been popular, with no shortage of mourners, the funeral procession and burial was accompanied by Kites of Nephthys (always women) who were paid to lament loudly throughout the proceedings. They sang The Lamentation of Isis and Nephthys, which originated in the myth of the two sisters weeping over the death of Osiris, and were supposed to inspire others at the funeral to a show of emotion.As in other ancient cultures, remembrance of the dead ensured their continued existence in the afterlife and a great showing of grief at a funeral was thought to have echoes in the Hall of Truth (also known as The Hall of Osiris) where the soul of the departed was heading. From the Old Kingdom Period on, the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony was performed either before the funeral procession or just prior to placing the mummy in the tomb.

This ceremony again underscores the importance of the physical body in that it was conducted in order to reanimate the corpse for continued use by the soul. A priest would recite spells as he used a ceremonial blade to touch the mouth of the corpse (so it could again breathe, eat, and drink) and the arms and legs so it could move about in the tomb. Once the body was laid to rest and the tomb sealed, other spells and prayers, such as The Litany of Osiris (or, in the case of a pharaoh, the spells known as The Pyramid Texts) were recited and the deceased was then left to begin the journey to the afterlife.

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN RELIGION : Egyptian religion was a combination of beliefs and practices which, in the modern day, would include magic, mythology, science, medicine, psychiatry, spiritualism, herbology, as well as the modern understanding of'religion' as belief in a higher power and a life after death. Religion played a part in every aspect of the lives of the ancient Egyptians because life on earth was seen as only one part of an eternal journey, and in order to continue that journey after death, one needed to live a life worthy of continuance. During one's life on earth, one was expected to uphold the principle of ma'at (harmony) with an understanding that one's actions in life affected not only one's self but others' lives as well, and the operation of the universe. People were expected to depend on each other to keep balance as this was the will of the gods to produce the greatest amount of pleasure and happiness for humans through a harmonious existence which also enabled the gods to better perform their tasks. By honoring the principle of ma'at (personified as a goddess of the same name holding the white feather of truth) and living one's life in accordance with its precepts, one was aligned with the gods and the forces of light against the forces of darkness and chaos, and assured one's self of a welcome reception in the Hall of Truth after death and a gentle judgment by Osiris, the Lord of the Dead.The underlying principle of Egyptian religion was known as heka (magic) personified in the god Heka. Heka had always existed and was present in the act of creation. He was the god of magic and medicine but was also the power which enabled the gods to perform their functions and allowed human beings to commune with their gods.

He was all-pervasive and all-encompassing, imbuing the daily lives of the Egyptians with magic and meaning and sustaining the principle of ma'at upon which life depended. This is exactly the relationship of Heka to the gods and human existence: he was the standard, the foundation of power, on which everything else depended. A god or goddess was invoked for a specific purpose, was worshipped for what they had given, but it was Heka who enabled this relationship between the people and their deities. The gods of ancient Egypt were seen as the lords of creation and custodians of order but also as familiar friends who were interested in helping and guiding the people of the land. The gods had created order out of chaos and given the people the most beautiful land on earth.

Egyptians were so deeply attached to their homeland that they shunned prolonged military campaigns beyond their borders for fear they would die on foreign soil and would not be given the proper rites for their continued journey after life. Egyptian monarchs refused to give their daughters in marriage to foreign rulers for the same reason. The gods of Egypt had blessed the land with their special favor, and the people were expected to honor them as great and kindly benefactors.

Long ago, they believed, there had been nothing but the dark swirling waters of chaos stretching into eternity. Out of this chaos (Nu) rose the primordial hill, known as the Ben-Ben, upon which stood the great god Atum (some versions say the god was Ptah) in the presence of Heka.

Atum looked upon the nothingness and recognized his aloneness, and so he mated with his own shadow to give birth to two children, Shu (god of air, whom Atum spat out) and Tefnut (goddess of moisture, whom Atum vomited out). Shu gave to the early world the principles of life while Tefnut contributed the principles of order. Leaving their father on the Ben-Ben, they set out to establish the world. In time, Atum became concerned because his children were gone so long, and so he removed his eye and sent it in search of them. While his eye was gone, Atum sat alone on the hill in the midst of chaos and contemplated eternity.

These tears, dropping onto the dark, fertile earth of the Ben-Ben, gave birth to men and women. These humans had nowhere to live, however, and so Shu and Tefnut mated and gave birth to Geb (the earth) and Nut (the sky). Geb and Nut, though brother and sister, fell deeply in love and were inseparable. Atum found their behaviour unacceptable and pushed Nut away from Geb, high up into the heavens. The two lovers were forever able to see each other but were no longer able to touch.

Nut was already pregnant by Geb, however, and eventually gave birth to Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys, and Horus - the five Egyptian gods most often recognized as the earliest (although Hathor is now considered to be older than Isis). These gods then gave birth to all the other gods in one form or another. The gods each had their own area of speciality. Bastet, for example, was the goddess of the hearth, homelife, women's health and secrets, and of cats. Hathor was the goddess of kindness and love, associated with gratitude and generosity, motherhood, and compassion. According to one early story surrounding her, however, she was originally the goddess Sekhmet who became drunk on blood and almost destroyed the world until she was pacified and put to sleep by beer which the gods had dyed red to fool her. When she awoke from her sleep, she was transformed into a gentler deity. Although she was associated with beer, Tenenet was the principle goddess of beer and also presided over childbirth. Beer was considered essential for one's health in ancient Egypt and a gift from the gods, and there were many deities associated with the drink which was said to have been first brewed by Osiris. An early myth tells of how Osiris was tricked and killed by his brother Set and how Isis brought him back to life. He was incomplete, however, as a fish had eaten a part of him, and so he could no longer rule harmoniously on earth and was made Lord of the Dead in the underworld. His son, Horus the Younger, battled Set for eighty years and finally defeated him to restore harmony to the land.Horus and Isis then ruled together, and all the other gods found their places and areas of expertise to help and encourage the people of Egypt. Among the most important of these gods were the three who made up the Theban Triad: Amun, Mut, and Knons (also known as Khonsu).

Defeated his rivals and united Egypt, elevating Thebes to the position of capital and its gods to supremacy. Amun, Mut, and Khons of Upper Egypt (where Thebes was located) took on the attributes of Ptah, Sekhment, and Khonsu of Lower Egypt who were much older deities. Amun became the supreme creator god, symbolized by the sun; Mut was his wife, symbolized by the sun's rays and the all-seeing eye; and Khons was their son, the god of healing and destroyer of evil spirits.

These three gods were associated with Ogdoad of Hermopolis, a group of eight primordial deities who embodied the qualities of primeval matter, such as darkness, moistness, and lack of boundaries or visible powers. It usually consisted of four deities doubled to eight by including female counterparts (Pinch, 175-176). The Ogdoad (pronounced OG-doh-ahd) represented the state of the cosmos before land rose from the waters of chaos and light broke through the primordial darkness and were also referred to as the Hehu (`the infinities').

They were Amun and Amaunet, Heh and Hauhet, Kek and Kauket, and Nun and Naunet each representing a different aspect of the formless and unknowable time before creation: Hiddenness (Amun/Amaunet), Infinity (Heh/Hauhet), Darkness (Kek/Kauket), and the Abyss (Nut/Naunet). The Ogdoad are the best example of the Egyptian's insistence on symmetry and balance in all things embodied in their male/female aspect which was thought to have engendered the principle of harmony in the cosmos before the birth of the world. The Egyptians believed that the earth (specifically Egypt) reflected the cosmos.The stars in the night sky and the constellations they formed were thought to have a direct bearing on one's personality and future fortunes. The gods informed the night sky, even traveled through it, but were not distant deities in the heavens; the gods lived alongside the people of Egypt and interacted with them daily. Trees were considered the homes of the gods and one of the most popular of the Egyptian deities, Hathor, was sometimes known as "Mistress of the Date Palm" or "The Lady of the Sycamore" because she was thought to favor these particular trees to rest in or beneath. Scholars Oakes and Gahlin note that Presumably because of the shade and the fruit provided by them, goddesses associated with protection, mothering, and nurturing were closely associated with [trees].

Hathor, Nut, and Isis appear frequently in the religious imagery and literature [in relation to trees]. Plants and flowers were also associated with the gods, and the flowers of the ished tree were known as "flowers of life" for their life-giving properties. Eternity, then, was not an ethereal, nebulous concept of some'heaven' far from the earth but a daily encounter with the gods and goddesses one would continue to have contact with forever, in life and after death.In order for one to experience this kind of bliss, however, one needed to be aware of the importance of harmony in one's life and how a lack of such harmony affected others as well as one's self. The'gateway sin' for the ancient Egyptians was ingratitude because it threw one off balance and allowed for every other sin to take root in a person's soul. Once one lost sight of what there was to be grateful for, one's thoughts and energies were drawn toward the forces of darkness and chaos. This belief gave rise to rituals such as The Five Gifts of Hathor in which one would consider the fingers of one's hand and name the five things in life one was most grateful for. One was encouraged to be specific in this, naming anything one held dear such as a spouse, one's children, one's dog or cat, or the tree by the stream in the yard.

As one's hand was readily available at all times, it would serve as a reminder that there were always five things one should be grateful for, and this would help one to maintain a light heart in keeping with harmonious balance. This was important throughout one's life and remained equally significant after one's death since, in order to progress on toward an eternal life of bliss, one's heart needed to be lighter than a feather when one stood in judgment before Osiris. According to the scholar Margaret Bunson: The Egyptians feared eternal darkness and unconsciousness in the afterlife because both conditions belied the orderly transmission of light and movement evident in the universe. They understood that death was the gateway to eternity. The Egyptians thus esteemed the act of dying and venerated the structures and the rituals involved in such a human adventure. The structures of the dead can still be seen throughout Egypt in the modern day in the tombs and pyramids which still rise from the landscape.There were structures and rituals after life, however, which were just as important. All nine of these aspects were part of one's earthly existence and, at death, the Akh (with the Sahu and Sechem) appeared before the great god Osiris in the Hall of Truth and in the presence of the Forty-Two Judges to have one's heart (Ab) weighed in the balance on a golden scale against the white feather of truth. One would need to recite the Negative Confession (a list of those sins one could honestly claim one had not committed in life) and then one's heart was placed on the scale. If one's heart was lighter than the feather, one waited while Osiris conferred with the Forty-Two Judges and the god of wisdom, Thoth, and, if considered worthy, was allowed to pass on through the hall and continue one's existence in paradise; if one's heart was heavier than the feather it was thrown to the floor where it was devoured by the monster Ammut (the gobbler), and one then ceased to exist.

Once through the Hall of Truth, one was then guided to the boat of Hraf-haf ("He Who Looks Behind Him"), an unpleasant creature, always cranky and offensive, whom one had to find some way to be kind and courteous to. By showing kindness to the unkind Hraf-haf, one showed one was worthy to be ferried across the waters of Lily Lake (also known as The Lake of Flowers) to the Field of Reeds which was a mirror image of one's life on earth except there was no disease, no disappointment, and no death. One would then continue one's existence just as before, awaiting those one loved in life to pass over themselves or meeting those who had gone on before. Although the Greek historian Herodotus claims that only men could be priests in ancient Egypt, the Egyptian record argues otherwise.

Women could be priests of the cult of their goddess from the Old Kingdom onward and were accorded the same respect as their male counterparts. Usually a member of the clergy had to be of the same sex as the deity they served. The cult of Hathor, most notably, was routinely attended to by female clergy (it should be noted that'cult' did not have the same meaning in ancient Egypt that it does today - cults were simply sects of one religion). Priests and Priestesses could marry, have children, own land and homes and lived as anyone else except for certain ritual practices and observances regarding purification before officiating. Bunson writes: In most periods, the priests of Egypt were members of a family long connected to a particular cult or temple.Priests recruited new members from among their own clans, generation after generation. This meant that they did not live apart from their own people and thus maintained an awareness of the state of affairs in their communities. They blessed amulets to ward off demons or increase fertility, and also performed exorcisms and purification rites to rid a home of ghosts. Their chief duty was to the god they served and the people of the community, and an important part of that duty was their care of the temple and the statue of the god within. Priests were also doctors in the service of Heka, no matter what other deity they served directly.

An example of this is how all the priests and priestesses of the goddess Serket (Selket) were doctors but their ability to heal and invoke Serket was enabled through the power of Heka. The temples of ancient Egypt were thought to be the literal homes of the deities they honored. Every morning the head priest or priestess, after purifying themselves with a bath and dressing in clean white linen and clean sandals, would enter the temple and attend to the statue of the god as they would to a person they were charged to care for. The doors of the sanctuary were opened to let in the morning light, and the statue, which always resided in the innermost sanctuary, was cleaned, dressed, and anointed with oil; afterwards, the sanctuary doors were closed and locked.

No one but the head priest was allowed such close contact with the god. Those who came to the temple to worship only were allowed in the outer areas where they were met by lesser clergy who addressed their needs and accepted their offerings. There were no official `scriptures' used by the clergy but the concepts conveyed at the temple are thought to have been similar to those found in works such as the Pyramid Texts, the later Coffin Texts, and the spells found in the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

Although the Book of the Dead is often referred to as `The Ancient Egyptian Bible' it was no such thing. The Book of the Dead is a collection of spells for the soul in the afterlife.

All three of these works deal with how the soul is to navigate the afterlife. Their titles (given by European scholars) and the number of grand tombs and statuary throughout Egypt, not to mention the elaborate burial rituals and mummies, have led many people to conclude that Egypt was a culture obsessed with death when, actually, the Egyptians were wholly concerned with life.The Book on Coming Forth by Day, as well as the earlier texts, present spiritual truths one would have heard while in life and remind the soul of how one should now act in the next phase of one's existence without a physical body or a material world. The soul of any Egyptian was expected to recall these truths from life, even if they never set foot inside a temple compound, because of the many religious festivals the Egyptians enjoyed throughout the year.

Religious festivals in Egypt integrated the sacred aspect of the gods seamlessly with the daily lives of the people. Egyptian scholar Lynn Meskell notes that religious festivals actualized belief; they were not simply social celebrations. They acted in a multiplicity of related spheres (Nardo, 99).There were grand festivals such as The Beautiful Festival of the Wadi in honor of the god Amun and lesser festivals for other gods or to celebrate events in the life of the community. There the oracles took place and the priests answered petitions. The statue of the god would be removed from the inner sanctuary to visit the members of the community and take part in the celebration; a custom which may have developed independently in Egypt or come from Mesopotamia where this practice had a long history.

The Beautiful Festival of the Wadi was a celebration of life, wholeness, and community, and, as Meskell notes, people attended this festival and visited the shrine to "pray for bodily integrity and physical vitality" while leaving offerings to the god or goddess as a sign of gratitude for their lives and health. Meskell writes: One may envisage a priest or priestess coming and collecting the offerings and then replacing the baskets, some of which have been detected archaeologically. The fact that these items of jewelry were personal objects suggests a powerful and intimate link with the goddess.Moreover, at the shrine site of Timna in the Sinai, votives were ritually smashed to signify the handing over from human to deity, attesting to the range of ritual practices occurring at the time. There was a high proportion of female donors in the New Kingdom, although generally tomb paintings tend not to show the religous practices of women but rather focus on male activities. The smashing of the votives signified one's surrender to the benevolent will of the gods.

A votive was anything offered in fulfillment of a vow or in the hopes of attaining some wish. While votives were often left intact, they were sometimes ritually destroyed to signify the devotion one had to the gods; one was surrendering to them something precious which one could not take back. There was no distinction at these festivals between those acts considered'holy' and those which a modern sensibility would label'profane'. The whole of one's life was open for exploration during a festival, and this included sexual activity, drunkenness, prayer, blessings for one's sex life, for one's family, for one's health, and offerings made both in gratitude and thanksgiving and in supplication. Families attended the festivals together as did teenagers and young couples and those hoping to find a mate.

Elder members of the community, the wealthy, the poor, the ruling class, and the slaves were all a part of the religious life of the community because their religion and their daily lives were completely intertwined and, through that faith, they recognized their individual lives were all an interwoven tapestry with every other. ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GRAVE GOODS : Grave Goods in Ancient Egypt.

The concept of the afterlife changed in different eras of Egypt's very long history, but for the most part, it was imagined as a paradise where one lived eternally. To the Egyptians, their country was the most perfect place which had been created by the gods for human happiness. The afterlife, therefore, was a mirror image of the life one had lived on earth - down to the last detail - with the only difference being an absence of all those aspects of existence one found unpleasant or sorrowful. One inscription about the afterlife talks about the soul being able to eternally walk beside its favorite stream and sit under its favorite sycamore tree, others show husbands and wives meeting again in paradise and doing all the things they did on earth such as plowing the fields, harvesting the grain, eating and drinking.In order to enjoy this paradise, however, one would need the same items one had during one's life. Tombs and even simple graves included personal belongings as well as food and drink for the soul in the afterlife. These items are known as'grave goods' and have become an important resource for modern-day archaeologists in identifying the owners of tombs, dating them, and understanding Egyptian history. Although some people object to this practice as'grave robbing,' the archaeologists who professionally excavate tombs are assuring the deceased of their primary objective: to live forever and have their name remembered eternally. According to the ancient Egyptians' own beliefs, the grave goods placed in the tomb would have performed their function many centuries ago.

Grave goods, in greater or lesser number and varying worth, have been found in almost every Egyptian grave or tomb which was not looted in antiquity. The articles one would find in a wealthy person's tomb would be similar to those considered valuable today: ornately crafted objects of gold and silver, board games of fine wood and precious stone, carefully wrought beds, chests, chairs, statuary, and clothing.

The finest example of a pharaoh's tomb, of course, is King Tutankhamun's from the 14th century B. Discovered by Howard Carter in 1922 A. But there have been many tombs excavated throughout ancient Egypt which make clear the social status of the individual buried there. Even those of modest means included some grave goods with the deceased.

The primary purpose of grave goods was not so show off the deceased person's status but to provide the dead with what they would need in the afterlife. The primary purpose of grave goods, though, was not so show off the deceased person's status but to provide the dead with what they would need in the afterlife. A wealthy person's tomb, therefore, would have more grave goods - of whatever that person favored in life - than a poorer person.

Favorite foods were left in the tomb such as bread and cake, but food and drink offerings were expected to be made by one's survivors daily. In the tombs of the upper-class nobles and royalty an offerings chapel was included which featured the offerings table. One's family would bring food and drink to the chapel and leave it on the table. The soul of the deceased would supernaturally absorb the nutrients from the offerings and then return to the afterlife.

This ensured one's continual remembrance by the living and so one's immortality in the next life. If a family was too busy to tend to the daily offerings and could afford it, a priest (known as the ka-priest or water-pourer) would be hired to perform the rituals. However the offerings were made, though, they had to be taken care of on a daily basis.

Deals with this precise situation. Khonsemhab finds and repairs the tomb and also promises that he will make sure offerings are provided from then on.The end of the manuscript is lost, but it is presumed the story ends happily for the ghost of Nebusemekh. Beer was the drink commonly provided with grave goods.

In Egypt, beer was the most popular beverage - considered the drink of the gods and one of their greatest gifts - and was a staple of the Egyptian diet. A wealthy person (such as Tutankhamun) was buried with jugs of freshly brewed beer whereas a poorer person would not be able to afford that kind of luxury. People were often paid in beer so to bury a jug of it with a loved one would be comparable to someone today burying their paycheck. Beer was sometimes brewed specifically for a funeral, since it would be ready, from inception to finish, by the time the corpse had gone through the mummification process. After the funeral, once the tomb had been closed, the mourners would have a banquet in honor of the dead person's passing from time to eternity, and the same brew which had been made for the deceased would be enjoyed by the guests; thus providing communion between the living and the dead. Among the most important grave goods was the shabti doll. Shabti were made of wood, stone, or faience and often were sculpted in the likeness of the deceased. In life, people were often called upon to perform tasks for the king, such as supervising or laboring on great monuments, and could only avoid this duty if they found someone willing to take their place. Since the afterlife was simply a continuation of the present one, people expected to be called on to do work for Osiris in the afterlife just as they had labored for the king. The shabti doll could be animated, once one had passed into the Field of Reeds, to assume one's responsibilities. The soul of the deceased could continue to enjoy a good book or go fishing while the shabti took care of whatever work needed to be done.Just as one could not avoid one's obligations on earth, though, the shabti could not be used perpetually. A shabti doll was good for only one use per year. People would commission as many shabti as they could afford in order to provide them with more leisure in the afterlife.

Shabti dolls are included in graves throughout the length of Egypt's history. They were mass-produced, as many items were, and more are included in tombs and graves of every social class from then on. The poorest people, of course, could not even afford a generic shabti doll, but anyone who could, would pay to have as many as possible. A collection of shabtis, one for each day of the year, would be placed in the tomb in a special shabti box which was usually painted and sometimes ornamented. Instructions on how one would animate a shabti in the next life, as well as how to navigate the realm which waited after death, was provided through the texts inscribed on tomb walls and, later, written on papyrus scrolls.The Pyramid Texts are the oldest religious texts and were written on the walls of the tomb to provide the deceased with assurance and direction. When a person's body finally failed them, the soul would at first feel trapped and confused. The rituals involved in mummification prepared the soul for the transition from life to death, but the soul could not depart until a proper funeral ceremony was observed.

When the soul woke in the tomb and rose from its body, it would have no idea where it was or what had happened. In order to reassure and guide the deceased, the Pyramid Texts and, later, Coffin Texts were inscribed and painted on the inside of tombs so that when the soul awoke in the dead body it would know where it was and where it now had to go.

These texts eventually turned into The Egyptian Book of the Dead (whose actual title is The Book of Coming Forth by Day), which is a series of spells the dead person would need in order to navigate through the afterlife. Spell 6 from the Book of the Dead is a rewording of Spell 472 of the Coffin Texts, instructing the soul in how to animate the shabti. Once the person died and then the soul awoke in the tomb, that soul was led - usually by the god Anubis but sometimes by others - to the Hall of Truth (also known as The Hall of Two Truths) where it was judged by the great god Osiris. The soul would then speak the Negative Confession (a list of'sins' they could honestly say they had not committed such as'I have not lied, I have not stolen, I have not purposefully made another cry'), and then the heart of the soul would be weighed on a scale against the white feather of ma'at, the principle of harmony and balance. If the heart was found to be lighter than the feather, then the soul was considered justified; if the heart was heavier than the feather, it was dropped onto the floor where it was eaten up by the monster Amut, and the soul would then cease to exist.There was no'hell' for eternal punishment of the soul in ancient Egypt; their greatest fear was non-existence, and that was the fate of someone who had done evil or had purposefully failed to do good. If the soul was justified by Osiris then it went on its way. In some eras of Egypt, it was believed the soul then encountered various traps and difficulties which they would need the spells from The Book of the Dead to get through. In most eras, though, the soul left the Hall of Truth and traveled to the shores of Lily Lake (also known as The Lake of Flowers) where they would encounter the perpetually unpleasant ferryman known as Hraf-hef ("He Who Looks Behind Himself") who would row the soul across the lake to the paradise of the Field of Reeds. Hraf-hef was the'final test' because the soul had to find some way to be polite, forgiving, and pleasant to this very unpleasant person in order to cross.

Once across the lake, the soul would find itself in a paradise which was the mirror image of life on earth, except lacking any disappointment, sickness, loss, or - of course - death. Reuniting with loved ones and living eternally with the gods was the hope of the afterlife but equally so was being met by one's favorite pets in paradise. Pets were sometimes buried in their own tombs but, usually, with their master or mistress.

The two best examples of this are High Priestess Maatkare Mutemhat circa 1077-943 B. Who was buried with her mummified pet monkey and the Queen Isiemkheb circa 1069-943 B. Who was buried with her pet gazelle.Mummification was expensive, however, and especially the kind practiced on these two animals. They received top treatment in their mummification and this, of course, represented the wealth of their owners. There were three levels of mummification available: top-of-the-line where one was treated as a king (and received a burial in keeping with the glory of the god Osiris); middle-grade where one was treated well but not that well; and the cheapest where one received minimal service in mummification and burial. Still, everyone - rich or poor - provided their dead with some kind of preparation of the corpse and grave goods for the afterlife. Pets were treated very well in ancient Egypt and were represented in tomb paintings and grave goods such as dog collars.

The tomb of Tutankhamun contained dog collars of gold and paintings of his hunting hounds. Although modern day writers often claim that Tutankhamun's favorite dog was named Abuwtiyuw, who was buried with him, this is not correct.

Abuwtiyuw is the name of a dog from the Old Kingdom of Egypt who so pleased the king that he was given private burial and all the rites due a person of noble birth. , Akbaru, was greatly admired by his master and buried with him. The collars of dogs, which frequently gave their name, often were included as grave goods. Contained two ornamented dog collars of leather.These were dyed pink and decorated with images. One of them has horses and lotus flowers punctuated by brass studs while the other depicts hunting scenes and has the dog's name, Tantanuit, engraved on it.

These are two of the best examples of the kind of ornate work which went into dog collars in ancient Egypt. By the time of the New Kingdom, in fact, the dog collar was its own type of artwork and worthy to be worn in the afterlife in the presence of the gods. There was a significant philosophical shift where people questioned the reality of this paradise and emphasized making the most of life because nothing existed after death. Some scholars have speculated that this belief came about because of the turmoil of the First Intermediate Period which came before the Middle Kingdom, but there is no convincing evidence of this. Such theories are always based on the claim that the First Intermediate Period of Egypt was a dark time of chaos and confusion which it most certainly was not.The Egyptians always emphasized living life to its fullest - their entire culture is based on gratitude for life, enjoying life, loving every moment of life - so an emphasis on this was nothing new. What makes the Middle Kingdom belief so interesting, however, is its denial of immortality in an effort to make one's present life even more precious.

The literature of the Middle Kingdom expresses a lack of belief in the traditional view of paradise because people in the Middle Kingdom were more'cosmopolitan' than in earlier times and were most likely attempting to distance themselves from what they saw as'superstition'. The First Intermediate Period had elevated the different districts of Egypt, made their individual artistic expressions as valuable as the state-mandated art and literature of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, and people felt freer to express their personal opinions rather than just repeat what they had been told. This skepticism disappears during the time of the New Kingdom, and - for the most part - the belief in the paradise of the Field of Reeds was constant throughout Egypt's history. A component of this belief was the importance of grave goods which would serve the deceased in the afterlife just as well as they had on the earthly plane. ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CULTURE : Ancient Egyptian culture flourished between circa 5500 B. With the rise of technology (as evidenced in the glass-work of faience) and 30 B. With the death of Cleopatra VII, the last Ptolemaic ruler of Egypt. It is famous today for the great monuments which celebrated the triumphs of the rulers and honored the gods of the land. The culture is often misunderstood as having been obsessed with death but, had this been so, it is unlikely it would have made the significant impression it did on other ancient cultures such as Greece and Rome. The Egyptian culture was, in fact, life affirming, as the scholar Salima Ikram writes. Judging by the numbers of tombs and mummies that the ancient Egyptians left behind, one can be forgiven for thinking that they were obsessed by death.However, this is not so. The Egyptians were obsessed by life and its continuation rather than by a morbid fascination with death.

The tombs, mortuary temples and mummies that they produced were a celebration of life and a means of continuing it for eternity. For the Egyptians, as for other cultures, death was part of the journey of life, with death marking a transition or transformation after which life continued in another form, the spiritual rather than the corporeal. This passion for life imbued in the ancient Egyptians a great love for their land as it was thought that there could be no better place on earth in which to enjoy existence. While the lower classes in Egypt, as elsewhere, subsisted on much less than the more affluent, they still seem to have appreciated life in the same way as the wealthier citizens.

This is exemplified in the concept of gratitude and the ritual known as The Five Gifts of Hathor in which the poor laborers were encouraged to regard the fingers of their left hand (the hand they reached with daily to harvest field crops) and to consider the five things they were most grateful for in their lives. Ingratitude was considered a `gateway sin' as it led to all other types of negative thinking and resultant behavior. Once one felt ungrateful, it was observed, one then was apt to indulge oneself further in bad behavior. The Cult of Hathor was very popular in Egypt, among all classes, and epitomizes the prime importance of gratitude in Egyptian culture.Religion was an integral part of the daily life of every Egyptian. As with the people of Mesopotamia, the Egyptians considered themselves co-laborers with the gods but with an important distinction: whereas the Mesopotamian peoples believed they needed to work with their gods to prevent the recurrence of the original state of chaos, the Egyptians understood their gods to have already completed that purpose and a human's duty was to celebrate that fact and give thanks for it. So-called `Egyptian mythology' was, in ancient times, as valid a belief structure as any accepted religion in the modern day.

Egyptian religion taught the people that, in the beginning, there was nothing but chaotic swirling waters out of which rose a small hill known as the Ben-Ben. Atop this hill stood the great god Atum who spoke creation into being by drawing on the power of Heka, the god of magic. Magic informed the entire civilization and Heka was the source of this creative, sustaining, eternal power. In another version of the myth, Atum creates the world by first fashioning Ptah, the creator god who then does the actual work. Another variant on this story is that Ptah first appeared and created Atum. Another, more elaborate, version of the creation story has Atum mating with his shadow to create Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture) who then go on to give birth to the world and the other gods. From this original act of creative energy came all of the known world and the universe.It was understood that human beings were an important aspect of the creation of the gods and that each human soul was as eternal as that of the deities they revered. Death was not an end to life but a re-joining of the individual soul with the eternal realm from which it had come. The Egyptian concept of the soul regarded it as being comprised of nine parts: the Khat was the physical body; the Ka one's double-form; the Ba a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens; Shuyet was the shadow self; Akh the immortal, transformed self, Sahu and Sechem aspects of the Akh; Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil; Ren was one's secret name. An individual's name was considered of such importance that an Egyptian's true name was kept secret throughout life and one was known by a nickname.

Knowledge of a person's true name gave one magical powers over that individual and this is among the reasons why the rulers of Egypt took another name upon ascending the throne; it was not only to link oneself symbolically to another successful pharaoh but also a form of protection to ensure one's safety and help guarantee a trouble-free journey to eternity when one's life on earth was completed. According to the historian Margaret Bunson.

Eternity was an endless period of existence that was not to be feared by any Egyptian. The term `Going to One's Ka' (astral being) was used in each age to express dying. The hieroglyph for a corpse was translated as `participating in eternal life'. The tomb was the `Mansion of Eternity' and the dead was an Akh, a transformed spirit. The famous Egyptian mummy (whose name comes from the Persian and Arabic words for `wax' and `bitumen', muum and mumia) was created to preserve the individual's physical body (Khat) without which the soul could not achieve immortality. As the Khat and the Ka were created at the same time, the Ka would be unable to journey to The Field of Reeds if it lacked the physical component on earth.The gods who had fashioned the soul and created the world consistently watched over the people of Egypt and heard and responded to, their petitions. A famous example of this is when Ramesses II was surrounded by his enemies at the Battle of Kadesh 1274 B. And, calling upon the god Amun for aid, found the strength to fight his way through to safety. There are many far less dramatic examples, however, recorded on temple walls, stele, and on papyrus fragments. Papyrus (from which comes the English word `paper') was only one of the technological advances of the ancient Egyptian culture.

The Kahun Gynecological Papyrus circa 1800 B. Is an early treatise on women's health issues and contraception and the Edwin Smith Papyrus circa 1600 B. Is the oldest work on surgical techniques.

Dentistry was widely practiced and the Egyptians are credited with inventing toothpaste, toothbrushes, the toothpick, and even breath mints. They created the sport of bowling and improved upon the brewing of beer as first practiced in Mesopotamia. The Egyptians did not, however, invent beer.

This popular fiction of Egyptians as the first brewers stems from the fact that Egyptian beer more closely resembled modern-day beer than that of the Mesopotamians. Glass working, metallurgy in both bronze and gold, and furniture were other advancements of Egyptian culture and their art and architecture are famous world-wide for precision and beauty. Personal hygiene and appearance was valued highly and the Egyptians bathed regularly, scented themselves with perfume and incense, and created cosmetics used by both men and women. The practice of shaving was invented by the Egyptians as was the wig and the hairbrush. The water clock was in use in Egypt, as was the calendar.

Some have even suggested that they understood the principle of electricity as evidenced in the famous Dendera Light engraving on the wall of the Hathor Temple at Dendera. The images on the wall have been interpreted by some to represent a light bulb and figures attaching said bulb to an energy source. This interpretation, however, has been largely discredited by the academic community. In daily life, the Egyptians seem little different from other ancient cultures. Like the people of Mesopotamia, India, China, and Greece, they lived, mostly, in modest homes, raised families, and enjoyed their leisure time.A significant difference between Egyptian culture and that of other lands, however, was that the Egyptians believed the land was intimately tied to their personal salvation and they had a deep fear of dying beyond the borders of Egypt. It was thought that the fertile, dark earth of the Nile River Delta was the only area sanctified by the gods for the re-birth of the soul in the afterlife and to be buried anywhere else was to be condemned to non-existence. Because of this devotion to the homeland, Egyptians were not great world-travelers and there is no `Egyptian Herodotus' to leave behind impressions of the ancient world beyond Egyptian borders. Even in negotiations and treaties with other countries, Egyptian preference for remaining in Egypt was dominant. The historian Nardo writes, Though Amenophis III had joyfully added two Mitanni princesses to his harem, he refused to send an Egyptian princess to the sovereign of Mitanni, because, `from time immemorial a royal daughter from Egypt has been given to no one.

This is not only an expression of the feeling of superiority of the Egyptians over the foreigners but at the same time and indication of the solicitude accorded female relatives, who could not be inconvenienced by living among `barbarians'. Further, within the confines of the country people did not travel far from their places of birth and most, except for times of war, famine or other upheaval, lived their lives and died in the same locale. As it was believed that one's afterlife would be a continuation of one's present (only better in that there was no sickness, disappointment or, of course, death), the place in which one spent one's life would constitute one's eternal landscape. The yard and tree and stream one saw every day outside one's window would be replicated in the afterlife exactly. This being so, Egyptians were encouraged to rejoice in and deeply appreciate their immediate surroundings and to live gratefully within their means.The concept of ma'at (harmony and balance) governed Egyptian culture and, whether of upper or lower class, Egyptians endeavored to live in peace with their surroundings and with each other. Among the lower classes, homes were built of mud bricks baked in the sun. The more affluent a citizen, the thicker the home; wealthier people had homes constructed of a double layer, or more, of brick while poorer people's houses were only one brick wide. Wood was scarce and was only used for doorways and window sills (again, in wealthier homes) and the roof was considered another room in the house where gatherings were routinely held as the interior of the homes were often dimly lighted.

Clothing was simple linen, un-dyed, with the men wearing a knee-length skirt (or loincloth) and the women in light, ankle-length dresses or robes which concealed or exposed their breasts depending on the fashion at a particular time. It would seem that a woman's level of undress, however, was indicative of her social status throughout much of Egyptian history. Dancing girls, female musicians, and servants and slaves are routinely shown as naked or nearly naked while a lady of the house is fully clothed, even during those times when exposed breasts were a fashion statement. Even so, women were free to dress as they pleased and there was never a prohibition, at any time in Egyptian history, on female fashion. A woman's exposed breasts were considered a natural, normal, fashion choice and was in no way deemed immodest or provocative. It was understood that the goddess Isis had given equal rights to both men and women and, therefore, men had no right to dictate how a woman, even one's own wife, should attire herself. Children wore little or no clothing until puberty. Marriages were not arranged among the lower classes and there seems to have been no formal marriage ceremony.A man would carry gifts to the house of his intended bride and, if the gifts were accepted, she would take up residence with him. The average age of a bride was 13 and that of a groom 18-21.

A contract would be drawn up portioning a man's assets to his wife and children and this allotment could not be rescinded except on grounds of adultery (defined as sex with a married woman, not a married man). The historian Thompson writes, Egypt treated its women better than any of the other major civilizations of the ancient world. The Egyptians believed that joy and happiness were legitimate goals of life and regarded home and family as the major source of delight. Because of this belief, women enjoyed a higher prestige in Egypt than in any other culture of the ancient world.While the man was considered the head of the house, the woman was head of the home. She raised the children of both sexes until, at the age or four or five, boys were taken under the care and tutelage of their fathers to learn their profession (or attend school if the father's profession was that of a scribe, priest, or doctor). Girls remained under the care of their mothers, learning how to run a household, until they were married.

Women could also be scribes, priests, or doctors but this was unusual because education was expensive and tradition held that the son should follow the father's profession, not the daughter. Marriage was the common state of Egyptians after puberty and a single man or woman was considered abnormal. The higher classes, or nobility, lived in more ornate homes with greater material wealth but seem to have followed the same precepts as those lower on the social hierarchy. But only those of means could afford a quality playing board. This did not seem to stop poorer people from playing the game, however; they merely played with a less ornate set.

Watching wrestling matches and races and engaging in other sporting events, such as hunting, archery, and sailing, were popular among the nobility and upper class but, again, were enjoyed by all Egyptians in as much as they could be afforded (save for large animal hunting which was the sole provenance of the ruler and those he designated). Feasting at banquets was a leisure activity only of the upper class although the lower classes were able to enjoy themselves in a similar (though less lavish) way at the many religious festivals held throughout the year. Swimming and rowing were extremely popular among all classes. The Roman writer Seneca observed common Egyptians at sport the Nile River and described the scene: The people embark on small boats, two to a boat, and one rows while the other bails out water.